As I peer through the glass doors of a large laboratory space, I quietly enjoy the irony of what Dr Ann Clarke is saying to me.

The co-founder, with her husband Professor Brian Clarke, of an international project to collect and store the DNA of endangered animal species, Ann breezily informs me that “unfortunately we’ve had a small flood in the specimen room so I can’t show you around”. The Frozen Ark project is flooded out. Maybe someone up there has a sense of humour.

Every year the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) update their ‘Red List’ of threatened species which evaluates the conservation status of the world’s flora and fauna. One species holds the comfortable position of Least Concern being as it is “widely distributed, adaptable, currently increasing”. That species is homo sapien – us.

Every year the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) update their ‘Red List’ of threatened species which evaluates the conservation status of the world’s flora and fauna. One species holds the comfortable position of Least Concern being as it is “widely distributed, adaptable, currently increasing”. That species is homo sapien – us.

But many others are facing eternal erasure as human populations proliferate across our planet apace, with habitat loss and species extinction the regrettably all too common endgame.

Among caveats and cautions about the difficulty of estimating such things, in 2011 the IUCN calculated that one in four of the world’s mammal species are under threat, with one in three amphibians facing a similar fate.

It was against this somewhat depressing backdrop that Anne and Brian ‘built’ their Frozen Ark.

Using cryopreservation technology to preserve DNA in liquid nitrogen at minus 80 degrees celsius, the Frozen Ark consortium currently holds 48,000 samples from more than 5,500 threatened and endangered animal species in labs around the world, including the original site at the University of Nottingham where Ann and Brian still work. The project is not shy when it comes to justifying itself. It will, so the leaflet I’m handed proudly states, ‘ensure that millions of years of evolution are not lost and generations to come will have a crucial knowledge and appreciation of the world’s creatures’. But the story really begins on a Polynesian Island in 1960.

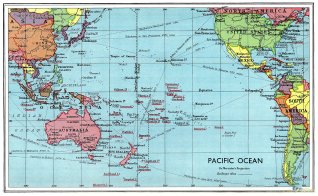

Over a thirty year period from the 1960s, Ann and Brian Clarke went on numerous expeditions to the Polynesian islands of Tahiti, Bororo and Maria to study the effects of geographical isolation on species. With a ring of high vaulting mountains enclosing verdant valleys below, they found that several species of snail had been cut off from the outside world. Like Darwin on the Galapagos islands, Ann and Brian couldn’t resist the opportunity to explore this ‘natural laboratory’.

Over a thirty year period from the 1960s, Ann and Brian Clarke went on numerous expeditions to the Polynesian islands of Tahiti, Bororo and Maria to study the effects of geographical isolation on species. With a ring of high vaulting mountains enclosing verdant valleys below, they found that several species of snail had been cut off from the outside world. Like Darwin on the Galapagos islands, Ann and Brian couldn’t resist the opportunity to explore this ‘natural laboratory’.

At around the same time, the colonial powers that be – the French government – introduced edible snails to the islands, but these alien intruders started to compete with the indigenous Partula snails Ann and Brian were studying. The French then introduced a second carnivorous species to control the edibles, but sadly they preferred the taste of Polynesia’s indigenous populations. “It was Brian who quickly released that conservation was crucial to protect threatened species” says Ann, who accompanied Brian on these Polynesian expeditions as “chief snail collector”, sleeping on deck to look after her slimy charges on the ocean voyage home.

Having exhaustively collected and archived specimens from all 160 species of Partula snail, the couple realised that no-one was doing the same for other threatened species. “Zoos were collecting gametes for their breeding programmes and museums were collecting specimens, but nobody was preserving DNA” says Ann. “Museums are generally very good, they never throw anything away, but they tend to preserve specimens in formalin or alcohol which generally ruins any genetic material”. And so, with no-one working to collect, store and preserve the DNA of endangered species, in 2000 the Frozen Ark project was born.

In order to explain the Frozen Ark it is tempting to invoke the 1992 Steven Spielberg film Jurassic Park, and the cloning of dinosaurs from blood contained in a prehistoric mosquito trapped in amber. But Ann tells me, with a hint of wry disappointment in her voice that “yes, everyone does that, it’s a favourite line amongst journalists”. So I won’t. Instead I’ll liken it to God’s external hard drive, backing up copies of all his creations in case the world populations were to ‘crash’ which, as the IUCN Red List makes plain, many are.

In order to explain the Frozen Ark it is tempting to invoke the 1992 Steven Spielberg film Jurassic Park, and the cloning of dinosaurs from blood contained in a prehistoric mosquito trapped in amber. But Ann tells me, with a hint of wry disappointment in her voice that “yes, everyone does that, it’s a favourite line amongst journalists”. So I won’t. Instead I’ll liken it to God’s external hard drive, backing up copies of all his creations in case the world populations were to ‘crash’ which, as the IUCN Red List makes plain, many are.

Although cloning technology is still striving to catch up with the Jurassic Park vision, in the present day the DNA samples held by the Ark are yielding important information about evolution. The Ark’s haul allows for comparative studies which shed light on evolutionary genetics, evolutionary trees and speciation – or the process by which a species branches off and evolves into a new species. “Our project has many important medical implications too” adds Ann. “For instance, certain species of jellyfish bioluminesce, which means they light themselves up using fluorescent pigments. Medical science is allowing us to inject these fluorescent pigments into humans in order to mark tumours, which allows doctors to study how they grow and spread”.

Despite this, the project is not without its critics. Ann recalls the time she was queuing for coffee at a WAZAA (World Association of Zoos and Aquariums) event. “A chap came up to me and said ‘you’re all wasting your time’ and walked off. I think many people are very pessimistic about conservation and fighting the tide of extinction. Perhaps we are wasting our time, but I think education is a crucial element.”

I wonder how conservation groups view the project. “We’re really the most depressed of ecologists, because basically we believe it’s too late for many endangered species” Ann admits. “Wild numbers of many species are too low for captive breeding programs to have any kind of impact. We’re really rather gloomy” she observes with a wry smile “so yes, perhaps that’s why we don’t get much support from conservation groups”.

![]() Our chat turns to a subject that has become something of an elephant in the room – the increasing number of our own species on the planet. “It’s an awkward subject” Ann concedes “because of course no-one would, or should, ever seriously consider ways to cap or stem human populations, but with more and more humans on the planet, it’s going to get much harder to save species as habitats come under increasing pressures from us”.

Our chat turns to a subject that has become something of an elephant in the room – the increasing number of our own species on the planet. “It’s an awkward subject” Ann concedes “because of course no-one would, or should, ever seriously consider ways to cap or stem human populations, but with more and more humans on the planet, it’s going to get much harder to save species as habitats come under increasing pressures from us”.

But she is optimistic that education could be the key. She tells me an anecdote about Madagascar, where hardwood trees were felled to produce furniture for the West. The practice was destroying lemur habitats, until people in the US started to hear where the wood was coming from. “It appears that exports of Madagascan hardwood are now falling. So maybe education is the key, maybe people will do the right thing given all the facts, maybe there is hope”. I start to think that maybe Ann isn’t such a gloomy ecologist after all.

The Frozen Ark has much in common with the Millennium Seed Bank (MSB) Partnership at Kew Gardens, the largest single site plant conservation project in the world. “I suppose the area of our work that brings us closest to the Frozen Ark” explains Professor Hugh Pritchard, Head of Research at Kew’s Seed Conservation Department, “is that we are developing new methods for the protection of samples stored at very low temperatures”. The Seed Bank works with a network of partners across 50 countries, and has already managed to bank 10% of the world’s wild plant species. What the Frozen Ark is doing for endangered animals, the MSB is doing for wild plants.

The Frozen Ark has much in common with the Millennium Seed Bank (MSB) Partnership at Kew Gardens, the largest single site plant conservation project in the world. “I suppose the area of our work that brings us closest to the Frozen Ark” explains Professor Hugh Pritchard, Head of Research at Kew’s Seed Conservation Department, “is that we are developing new methods for the protection of samples stored at very low temperatures”. The Seed Bank works with a network of partners across 50 countries, and has already managed to bank 10% of the world’s wild plant species. What the Frozen Ark is doing for endangered animals, the MSB is doing for wild plants.

Wild plant species from northern latitudes are built for periods of dormancy, and so freezing and storing poses relatively little problem. But for the 50-65% (estimates vary) of the earth’s flowering plants found in humid tropical rainforests, the challenge of preserving and storing their seeds is much greater, as Hugh Explains. “Before freezing we need to artificially dry our seeds to between 3 and 7% of their original moisture content, which is effectively desert conditions. Removing this much moisture often kills them, so the development of more effective cryoprotectants is a vital part of our work”.

It is only relatively recently that the technical challenges involved in freezing and storing living materials have been overcome. “There has been an empiricism to the work for the 30 years I’ve been involved in tissue storage” explains Hugh “but the 1990s heralded two significant breakthroughs”.

The breakthroughs in question were encapsulation in an algaenate bead (protective bubbles made of a seaweed extract) and the development of Plant Vitrification Solutions, or PVS. The former allowed plant seeds to be placed inside a protective droplet that gave researchers more control over the seed, but it’s PVS (which dehydrate cells to prevent deadly ice formation) that just might prove to the holy grail of cryopreservation. “PVS looks like it might be a generic solution. It has already worked with more than 100 plant species”.

As I gaze at phalanxes of specimen containers in the flood-hit labs of the Frozen Ark, I’m reminded of the words of American naturalist Edward Osborne Wilson, who said “if all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos”. One only need recall the recent collapse in honey bee numbers to grasp Osborne’s point.

But perhaps it’s Homer Simpson’s uncharacteristically sage observation that beer is “the cause of, and solution to, all of life’s problems” that hits the nail on the head. We are the cause of extinctions, but through projects like the Frozen Ark and MSB, which have just as much in common with archivism or chronic hoarding than they do with crusading conservationism, we are also the potential solution.

August 2012